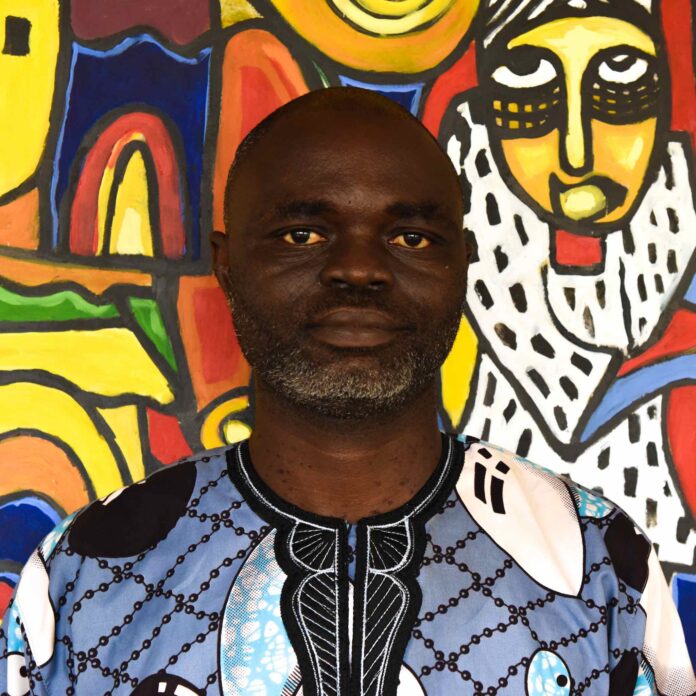

Magisterial and distinguished in the global discourse on exilic studies in all its forms and ferments, Professor Senayon Olaoluwa embodies the power of English literature in conveying a wide range of sociohistorical, political, and ideological contexts, especially with diaspora and transnational realities.

With a background in English and Literary Studies for his first degree at Ogun State University (now Olabisi Onabanjo University), specialisation in Literature at his Master’s degree from Nigeria’s premier University, the University of Ibadan, and a specialisation in African Literature at the University of Witwatersrand, South Africa, Professor Senayon’s critical and creative imagining and research in diaspora studies is a cynosure of global scholarship. His works examine the experiences, cultures, and social structures of dispersed ethnic populations.

Just when global interdisciplinary thinkers are still savouring the brilliance and beauty of his concept of Monotony of Natural Agency (which frames the triumph of “late arrivals” over “early arrivals” in a discourse of human evolution as a series of displacement and struggles), Professor Senayon dropped yet another theoretical cracker in the concept of Extalgia. The theory, an antithesis to the popular idea of nostalgia, describes the unique suffering, grief, and creativity experienced by those left behind in their homeland due to the migration of their loved ones.

This interview is a product of a stimulating engagement held on the International Day of the African Diaspora on July 1, 2025, hosted by the Graduate Research Clinic, and deftly moderated by Opeyemi Mishael, with a few contributions from scholars on the GRC page. Among other interesting (known and little-known) facts about Professor Senayon, the session zeroed in on the meat and crux of Extalgia beyond its conceptual description and academic derivatives that have ever been read or heard. It provides a firsthand walk-through on the curious conceptual phenomenon, as Professor Senayon describes it, but even goes deeper to mirror the distinguished Professor’s aspirations for theoretical agency in emerging African scholars to the end that there will be greater push for the development of new concepts and new mentality of theoretical originality regardless of spatial situation in the Global South.

You have come too far not to take a deep dive.

Excerpts:

To get us started, could you briefly introduce yourself, your academic background, and your current role, for the benefit of those who may not know your work?

My name is Senayon Olaoluwa, a Professor of Diaspora and Transnational Studies at the Institute of African Studies, University of Ibadan, where I also double as the inaugural Director of the TETFUND Centre of Excellence for Diaspora Studies.

My background is in English and Literary Studies. I obtained my honours from the then Ogun State University, now known as Olabisi Onabanjo University in Ago-Iwoye, and I did my master’s with specialisation in Literature at the Department of English, University of Ibadan.

I obtained my PhD from the University of the Witwatersrand in the Humanities, with specialisation in African Literature. More specifically, my doctoral research was on the politics of exile in African poetry, and that investigation set the tone, I would say, for my ultimate specialisation in Diaspora and Transnational Studies.

Let’s begin by unpacking the concept itself. ‘Extalgia’ is a striking term – one that immediately invites curiosity…

You have asked an interesting question, I must say, because even for me, Extalgia remains a particularly curious conceptual phenomenon, in addition to the fact that it’s a brainchild of several decades. The first consciousness of it—even when I couldn’t wrap my head around it—was in the 1990s during my undergraduate days. I think I was in my third year when we took a course in African, African American, and Caribbean literature. We read, among other texts, George Lamming’s In the Castle of My Skin. There is a sense in which those of us in literature, and I think others who are enthusiastic about that area of knowledge, can embody the fictive world that is created in the texts they read. You can identify with characters, you can begin to feel what they feel, and sometimes, years after, you are always reconnecting with fictive characters as though they existed in real life.

That was it for me. There was this incident between Boy G and his mother, who, in contemporary parlance, you would refer to as a single mother. But in migration studies, that is the case of a left-behind mother with a son. And from the beginning to the end, the father or husband never comes back.

The mother then decides, in a very deliberate way, to ensure that the boy is a success through education. And the boy does succeed, completing his elementary school education in a society where, out of every ten children, maybe only five make it to high school, and of those, only one or two can scale through.

So, Boy G succeeds in a way that is resounding because his success even fetches him an international offer. And naturally, everyone assumes that makes the mother a superstar, and that she should be happy her son is taking up such an opportunity.

Then it is the eve of his departure. And the mother begins to, well, you might say, throw tantrums about a cat. A cat that tries to eat up the fish she has been frying to celebrate her son’s success.

Generally, you discover that the mother goes through a form of grief, which I will later theorise as pre-departure extalgia, pre-departure emotional suffering, and that happens to many people. You do not just begin to feel the absence of people after they are gone; you begin to feel it even before they depart.

But in those days, the memory would not depart. And then, I went on to do other things, my master’s, my PhD… I began to teach in a Department of English, yet I still could not make sense of it, but the memory would not go away.

Finally, sometime in 2013, the University of Ibadan hired me to begin a new programme in Diaspora and Transnational Studies, a graduate program at the Institute of African Studies.

The first challenge I faced was: how do you say a new thing? I challenged myself not to simply repeat what is already being said in history, anthropology, sociology, international relations, literature, and other fields. The question became: how do you say something new? And of course, this brings up another dimension of scholarship. The fact that, to say something new, you must demonstrate a profound familiarity with what others have already said.

So, in the course of my engagement with the broad literature on migration across disciplines, I discovered a gap. And that gap is this: we have always tended to focus almost exclusively on the experiences, the traumas, the grief, the suffering, and the triumphs of migrant lives — of mobile lives — while completely undermining what happens to those left behind.

In the context of migration, I became particularly concerned with how we have iconized a concept like nostalgia. That is a term coined in the late 17th century to describe the pathological trauma of Swiss soldiers sent abroad, who were dying not of combat, but of a kind of unexplainable depression. Eventually, a medical scholar investigated and concluded that they were suffering from grief, not being at home. Nostalgia began as a medical term in the context of migration and gradually evolved into what we know it as today. There were probably medications, even then, to treat that depression caused by being far from home.

Now, when you read literature, anthropology, political science, or history, you discover that we have always elevated the experiences of mobile lives to a certain plane, one that we don’t associate, as it were, with the left behind or with immobile lives.

The question for me then becomes one of what I call the affective deficit—the emotional gap we tend to ignore in the experiences of those left behind. If those who migrate suffer grief, sorrow, or longing when remembering home and the people they left behind, are we saying that the people left behind feel nothing in return?

That, for me, became the decisive moment to interrogate the discourse of migration, to challenge assumptions about migrant lives, and to draw not just African scholars’ attention but the world’s attention to this affective deficit, especially now, when we are talking migration equity.

How do we discuss migration equity and give institutional attention to migrant lives through bodies like UNESCO, the Red Cross, IOM, and others, while lacking parallel institutions to care for the left behind? Not just those left geographically, but those emotionally and socially affected by the dispersal of their loved ones into other lands.

That, for me, is the beginning of it.

How does extalgia relate to or differ from concepts like nostalgia, longing, or melancholia?

At this point, I would like to go, if you permit me, into the etymology of extalgia. The first thing I did was to investigate the etymology of nostalgia, and I discovered it is a combination of two Greek words: nostos and algos. Nostos means home, and algos means grief. So, this thing we reference as homesickness is basically about some kind of grief that is caused by not being at home.

Now, with that understanding, I decided to derive a new terminology to capture and encapsulate the experiences of the left behind, especially those who go through pains, suffering, and all, as predicated on the dispersion of their loved ones into other lands.

So, I came up with extalgia by combining the idea of exodus or exit and algos, meaning suffering—a grief that is predicated on the dispersal, on the exit of loved ones into other lands. That’s how we’ve arrived at it, but I must also add that extalgia is not only about suffering. It is not only about grief. It’s also about the transcendental agency of the left behind.

They do not grieve forever about their brother or sister or father or uncle that’s moved to the U.S., or that’s moved to the U.K., and all. They ultimately take creative steps of transcendence to cope.

In the case of Boy G’s mother in The Castle of My Skin, and understandably, for those who have read my article, you’re going to discover that the theory is built substantially around that text because it all began with it.

You’re going to realize that there are efforts of transcendence on the part of Boy G’s mother. For her, it’s about ensuring that the boy succeeds, and that is extremely important.

When people are left behind, they find a way to move on. That is what I call creativity. Some would say coping strategies. And so, that also tells us that the left behind is not without agency, but there are also limits to their agentic transcendence because some people are not just able to cope. Some people try to get creative, and the creativity becomes disastrous.

There is a Nollywood movie, Gone, and it is exactly the case of a mother, but this time with two children left behind before the children could even gain consciousness. And Animashaun goes away for about 25 years, and then the mother has to cope. For her, just anything that can be done to cope. One of which would be to also engage in some sex work and do all manner of other things that moralists would say are improper. Now, in a bid to always defend his mother, the first son becomes a street fighter because everybody, his mates, and others, are always trying to refer to his mother as an ashewo, a prostitute. And he gets angry, turns violent, joins all the bad gangs, and all that. But now, between the mother and the son, these are creative efforts, you would say.

But these efforts have been channelled into, if you like, very destructive negative energies. They manifest as negative energies. And the daughter becomes a street dancer.

And that tells us that, and this is part of the argument, meaning, we have to transcend literature to begin to look at the empirical implications of all this. Boiling down to the fact that the left behind need systems of care to be able to cope. There are people whose relations, or we may even begin with aged people, who have children in Europe and America, Canada, and everywhere. Even when these children send them dollars, pounds sterling, and all, they still feel empty.

Some of them lose their minds. Others have fallen into depression, leading to cardiovascular challenges because they do not get adequate care. Because institutions have not evolved to decisively take care of the left behind. There is necessity, for instance, to have institutions of pre-departure counselling, psychology, and post-departure counselling for the left behind—and we can go on and on and on.

Let me add that extalgia is not only about the African experience. It is a concept; it is a theory to which all human races can relate. And all we need to do is go back to texts and experiences of people, and we realize that, irrespective of race, it is something we have tended to undermine. We have repressed it, because that is the standard—that is the received pedagogical standard across the world.

And let me share this anecdote with you: Sometime in 2023, I was at the University of Oxford for a fellowship, where I met one of the biggest scholars in Diaspora Studies, Professor Robin Cohen. When I began to share the concept of extalgia with him, he was initially like, “Oh, I think one or two scholars have dealt with this kind of experience. I think sometime in the 1970s.” And he pushed back and said, “Wait a minute… I don’t think they did it exactly the way you have done it.” And then he paid more attention. At a point, he became very sober and emotional. And then he said, “Oh, so… my aunt must have suffered extalgia in the early 1920s.”

And he began to confess to me that, “You know what, Senayon, I am of migrant descent. I am Jewish. And in the early 1920s, Jews in Lithuania were being persecuted. So, my father and my uncles left, but they left their sister behind. And later, we began to hear all manner of things about our auntie. It is now, with this notion of your extagia, that I can feel and understand what my auntie felt then.” And that was it. He became the promoter of extalgia, you know, inviting me to international meetings and all, and in a way that is beginning to tell everybody that, “Look, there is something we have always undermined, but we can no longer continue to ignore.”

And that is extalgia, because what the theory does is to invite us, if you like, to reconfigure what I call the circle of migration, to include the left behind.

And that informs why, for instance, again, during my stay at Oxford, I met a professor from the University of Iowa in the U.S. And he was like, “Oh my goodness, this is like a medical theory! We are going to do something about it.”

And so, we came together and put up a proposal for a grant at the College of Health Sciences at the University of Iowa. And we won that grant to examine, as it were, the nexus between mental health and being left behind. We have just concluded the fieldwork, and it’s amazing what the University of Iowa and the University of Ibadan have found out from the pilots in Ibadan about the left-behind relations—and what they go through, despite the dollars, when their loved ones are dispersed into other lands.

This is interesting. I feel like there’s a lot of emotion and meaning hidden behind that term. But even more compelling is the fact that this is not just a reinterpretation, it’s a new term you have introduced into the conversation on migration, African Studies, and the humanities that deserves attention. Seeing that this is novel, how long did it take you to develop and refine this diaspora theory?

Like I said earlier, I began to conceive, unconsciously, unconscious conception, the idea of extalgia through the retention of the memory of Boy G and his mother. And that’s like since the 1990s. And then it went on with me, because I always remember it with goose pimples all over. Stuff like it could have been me, it could have been my mother. It could have been Senayon and his mother and all that.

I mean, my father could have just gone away without returning, and all that. My mother could have fought hard for me to succeed. And then, a day to my departure, I could have just lost it emotionally. And then coming to the University of Ibadan to teach a new programme in Diaspora and Transnational Studies was it for me.

And so, I began to teach extalgia with the third set of our Diaspora and Transnational Studies students, the master’s class, and that was like 2016. And then, I kept on developing the idea.

I like throwing new concepts around for feedback from my students and debates. And I must say, they have always been incredible, because I always stress the imperative of saying new things, of developing new concepts, of not always waiting for the Global North to, you know, bring up these new notions.

And I remember that this same question was asked while I was at Oxford. A professor of sociology who took me out for lunch did that with the intention of possibly destroying the concept. But for about two hours, I mean, he kept on asking questions, to which I could provide answers persuasively.

And so, he ended up asking, “So tell me, how many years did it take you to develop this?”

Well, our research is impacted by our teaching, and vice versa. We only feed into existing legacies of originality from the Ibadan School of History, you know, to other such schools. So, we also have what we are humbly calling the Ibadan School of Diaspora Studies.

And so, we did this here and there. I kept on teaching extalgia right from, I think, 2016 or so. But it wasn’t until 2022, or was it during the COVID year, that I took time out to say: “This thing that I am always talking about in class, can I just put it down and let’s see how it goes?”

During a fellowship at the University of Bremen, in either 2020 or 2021, I was able to write this article. And because it’s something I have borne for decades, I would say that the article ended up writing itself. Because I think I wrote it within the space of, was it a week or a maximum of 10 days? Every day, I was doing like a thousand words, because there was a lot of mental editing that had gone into it.

The initial idea of it was to just do a journal article and go away with it. But by the time I was done with the first draft I had a broader sense of it. I said, “No, this is not just an article. This is a whole book.”

Ever since the publication of the first chapter, I have been working on the other chapters, and hopefully, the entire work will be ready next year for peer review. I have the Minnesota University Press in mind for the publication because of an interesting series they are doing called Ideas First.

How universally applicable is this concept? Is it contextually bound to certain geopolitical or cultural settings?

As I said, I met Professor Robin Cohen at Oxford, and he became very sober, saying, “Oh, with this explanation, my auntie must have suffered extalgia when my father and my uncles left her in Lithuania.” And he became sad, because they didn’t pay as much attention to the ordeals of his left-behind auntie then.

And that tells you how universal it is. A theory may have come from what we call the Global South, but it doesn’t mean it cannot assume a global application. Right now, there are conversations with universities in the Global North to go into empirical research across disciplines, including medicine. And it will interest you to know that the very first empirical research on extalgia is in the area of medicine – psychiatry, to be specific. And so, it is there and open for application beyond the African experience.

What does this idea mean for how we talk today about Africans living abroad and their continued ties to Africa, especially considering the effects of colonial history?

That is exactly the point. The depression, the melancholia that are associated with migrant mobile lives are also parallel sensibilities of the left behind, which we have always ignored. Precisely because there is always this undeclared issue around unequal power relations between mobile lives and those trapped in immobility.

So, even when migrants have returned home, they are still the ones to curate the homeland for us in the language, in the rubric of homecoming. And we don’t think that the left behind can speak for themselves. The depression and the melancholia – we need to address the ethical questions that are raised.

One of which is: How do we care for the left behind? What systems of care can we put in place to cater, as it were, to the peculiar needs of the left behind within the context of migration? We also need to understand what this means for our brothers and sisters abroad and how to get it right.

Migration is a universal human experience. People will continue to move from place to place. But what it means is that, rather than constructing some kind of toga of triumphalism around the experience of mobility, to the extent of completely ignoring what those left behind may be going through, it is necessary for us, at the national and international levels, to begin to think about strategies and institutions that can also cater, as it were, to the psychosocial, physical, and emotional needs of the left behind.

Given the intellectual weight of the term, I imagine it has wider implications, especially in fields engaging with postcolonial identity and movement. Do you see potential connections between this idea and other disciplines or areas of study beyond the medical angle? What should the Global South be paying attention to, particularly within interdisciplinary research?

Thank you very much for the question about the interdisciplinary orientation of extalgia. I remember that in the first article, which is just one of the chapters in the book I’m working on, the very last paragraph invites scholars and researchers across disciplines to engage extalgia. So, it just happened that the medical sciences are the first to embrace extalgia; surprisingly, you know, from literature to medicine.

In the pilot study we have conducted with the School of Health Sciences at the University of Iowa, the findings are particularly compelling. We’ve been able to establish the fact that there is indeed a logical nexus between being left behind and mental health. Meaning, this is something that needs serious attention. But we are also going to realize that other disciplines, whether psychology, anthropology, and so forth, can also make sense of extalgia. Extalgia is one theory that is so open and can be applied by any discipline.

I am sure, just like myself, so many people are anticipating the release of the book already…

Thank you very much, Opeyemi. I am trying hard to finish up with the last three chapters. I’m hoping to complete the final three between now and early next year, 2026, so that it can go into review. And yeah, we’re staying positive about it. I’m also excited about it, and I do hope that this can be one of our humble offers from the Ibadan School of Diaspora Studies to the world.

Hearing the story behind extalgia, it’s clear this idea came from seeing what was missing in the literature and naming it. For those coming into research, how can we begin that kind of work, developing concepts that respond to real gaps in discourse? What charge do you have for students, upcoming scholars, and researchers with regard to innovative research?

I think we have to accept the challenge of assuming what I call theoretical agency. Of course, you are likely to encounter frustrations as you push for the development of new concepts, because there are people in the Global North, including Black folks, who don’t think that if you are based in Nigeria or South Africa or Ghana or Somalia, you can come up with a theory. Or, if you must do that at all, you have to move to Canada, or the US, or the UK, or Germany. But the truth of the matter is that the agency for theorizing is imminent in every culture, in every location, and so we can always challenge ourselves. This is part of what we also encourage at the Institute of African Studies. I remember that a few weeks ago, a student in Cultural and Media Studies did his post-fieldwork, and in the course of his research, he was able to argue about the inadequacy of a particular theory he adopted because it could not sufficiently address the experience in the field. And so, he came up with his own theory to unpack the fieldwork, which his professor supported, and which we all commended. That’s the way to go. Even when people tell you, “Oh, you can’t do theory, you can’t relate to concepts,” you can. And that is exactly how to go about it. If you like, we must come up with a new understanding, a new mentality of theoretical originality, despite our location in Africa.

If extalgic emotions are absorbed within the matrix of post-departure trauma, does the phenomenon therefore hold any ground for forces that compel, or if you like, make inevitable, migrations in the capitalist world?

No amount of absorption can completely erase extalgic sensibilities when we do not offer the care that is needed. There is no amount of dollars, and I can tell you about an ongoing research where aged parents confess that despite the dollars their children send to them, they still feel empty. The emptiness they feel is not about asking their children to return to Nigeria. It is about the sense of abandonment they feel around them. Which means that formal structures have to be instituted for their care, and that’s the point we are making. Otherwise, we would have ended up subscribing to the capitalist tendencies that advocate for the wastage of human beings, through their reduction to matter and energy. And that is the point we are making.

How would you approach an imbrication and or reconciliation of your interesting theory with Afropolitanism and globalization? Given, of course, the presencing that technology offers today?

There is no amount of technology, in this age of the celebration of globalization and Afropolitanism, that can account for the traumatic sensibilities of those left behind. That is also why I argue that extalgia is a theory of intimacy. That does not mean that those loved ones who have migrated have to come back home, but there have to be systems of care to address their needs. I’ll share with you an anecdote from the course of developing the first paper on extalgia, which has now been published.

I was so excited reading over it and sharing some of the insights with a colleague. She suddenly became sad and sober. There was a mood swing, I would say. And the next thing she said was:

“No be wetin kill my mama be dat.”

I was like, “Sorry, I’m sorry to hear this. What happened?” She said, “This thing you have called extalgia was responsible for my mom’s death.”

I said, “How?”

She said: “You know, our eldest brother, who’s also our mother’s first son, travelled to Australia and he was like our mom’s favourite. And then every day, he would have video conversations with our mother on Zoom and all that. But despite all that, from time to time, our mom would say: ‘Hey, this boy went to Australia and will not return.’ Every day: ‘This boy went to Australia and will not come back.’ Yet she was speaking with the son every day. Ultimately, this woman fell into depression and died.”

And don’t forget, in medical science, we all know that one symptom of trauma is repetition. Yet this mother could have been taken care of in other ways. But because we have for so long ignored the grief of the left behind, so many people have simply died from not receiving care.