German-American writer, Charles Bukowski, once said: “If something burns your soul with purpose and desire, it’s your duty to be reduced to ashes by it. Any other form of existence will be yet another dull book in the library of life.” This, among a few other valuable ideals, is what governs Dr. Ademola Adesola’s drive in his multispectral contributory roles in society. A teacher, a researcher, a journalist, and a public analyst, the Nigerian-Canadian Assistant Professor of postcolonial literatures had a rich and engaging conversation with the Diaspora NG team, which has produced a must-read interview for many across different walks of life.

Dr. Adesola completed his doctorate at the University of Manitoba, Canada. His doctoral work on children at war attracted different awards, including the Dr. Vernon B. Rhodenizer Scholarship and the Berdie and Irvin Cohen Scholarship in Peace and Conflict Studies.

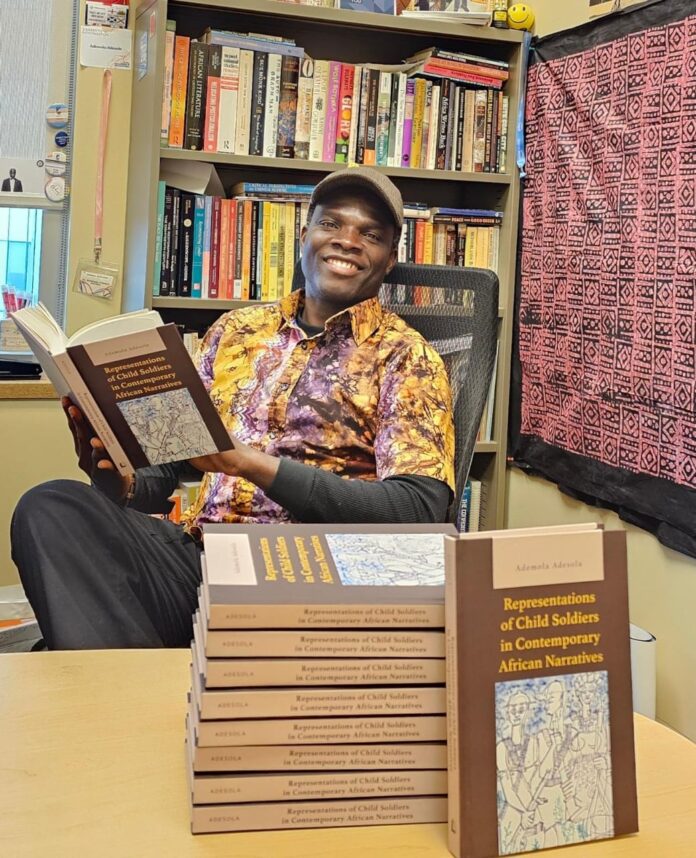

Dr. Adesola has published essays in different journals and book chapters on African and Black literatures. His new monograph, Representations of Child Soldiers in Contemporary African Narratives, examines the literary depictions of African child soldiers with a view to mapping the dominant factors that writers privilege in their depictions of child soldiering in sub-Saharan Africa. Dr Adesola’s scholarly endeavours have been recognized. In the 2024-2025 academic year at Mount Royal University, Dr. Adesola was the recipient of the Faculty of Arts Outstanding Scholar Award, which recognizes one tenured or tenure-track faculty member annually for excellence in scholarly activity. He was also nominated for the Education Category of the 2025 Calgary Black Chambers’ Calgary Black Achievement Awards.

In this interview, Dr Adesola brings to fore many interesting perspectives, including his conception of scholarship and intellectualism as an act of industry, an unpacking of his research interest in the complex intersection of childhood, warfare and literature (highlighting the concept of child soldiering), the concept of ‘love for elsewhere’ in the light of dense emigration from Nigeria (vis-a-vis the complicity of the Nigerian state in the brain-drain syndrome), and many more interesting insights.

Dr Adesola also discusses his navigation through the potentiality of dislocation and discovery in the diasporic realm, highlighting challenges and opportunities he encountered and his responses as demanded by each occasion.

This is definitely worth your time and attention.

Excerpts:

Your academic trajectory has been distinguished by numerous prestigious scholarships and accolades. To what do you attribute this remarkable success, and what counsel might you offer to aspiring scholars who hope to carve a similarly distinguished path?

Thank you for this opportunity to converse with you. I commend you and your team for the efforts you’re deploying into staging conversations with Nigerians in the diaspora. Such conversations are necessary.

My response to this question is that nothing works well like diligence. I give thorough attention to anything that I consider worth doing. I heed the demanding charge of that German-American writer, Charles Bukowski, which says, “If something burns your soul with purpose and desire, it’s your duty to be reduced to ashes by it. Any other form of existence will be yet another dull book in the library of life.” As a scholar, I prioritize assiduousness. I think being a scholar is synonymous with industry. The life of the mind demands consistent hard work, especially of time. While we don’t take up tasks to have our shoulders festooned with colourful epaulettes, the accolades that accompany our commitments as scholars only serve to energize us more.

May I also note that my own success isn’t limited to my culture of hard work. Aren’t there many diligent people out there who are less fortunate? In this regard, I’m reminded of a key proverb from one of Chinua Achebe’s novels, to wit: “Those whose palm kernels were cracked for them by a benevolent spirit should not forget to be humble.’’ No individual can ever attribute their accomplishments solely to their efforts. All human feats are a big river made possible by the generosity of varied tributaries. In my journey to success, I have been ably aided by different people. Those individuals paid attention to me; they took me seriously as I did myself. The invaluable munificence of family, friends, and strangers has proved pivotal in my progress in life.

So, my advice to burgeoning scholars is to privilege hard work. Give your work the best of yourself as you evolve. It’s a fact that what you haven’t accorded significant attention can’t compel others’ attention. In addition, ensure that you aren’t a loner. You need others; you need a community of experienced and productive minds. Young scholars need to cultivate the wisdom to meaningfully balance the demands of independence and community. A scholar without a useful community is miserable.

Your research probes the complex intersections of war, childhood, and literature—a fraught and profoundly human terrain. What first drew you to this scholarly focus, and in what ways has your Nigerian heritage shaped your intellectual and emotional engagement with these themes?

Thank you for this question. Obafemi Awolowo University was the place where I first had the inspiration for this research. And I remain eternally grateful to the teachers I encountered at the Department of English and Literary Studies in that institution. They cultured my mind well despite the exhausting but avoidable challenges they had to deal with. My interest in children and warfare began when I was completing a research project for my master’s programme in OAU. As I make clear in the introduction to my book, Representations of Child Soldiers in Contemporary African Narratives, two African war novels ignited my scholarly interest in the phenomenon of child soldiering and its recreated accounts. Those novels are Chimamanda Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun and Akachi Adimora-Ezeigbo’s Roses and Bullets, both being representations of the Nigeria-Biafra ethnopolitical conflict of 1967-1970. In each of those fictions are dissimilar portrayals of children mobilized as soldiers. I studied both texts for my MA research project and was interested mainly in how female Nigerian writers envision the conflict in contrast to the dominant ones from male authors. It was when reading those novels that the child soldier subject became apparent to me. I would thereafter do a cursory search about the subject. It was through that quick search that the floodgate of imagined accounts prioritizing militarized children opened to me. I immersed myself in them, but more importantly, I discovered the discourses championed by human rights and humanitarian organizations on African child soldiers.

What I encountered in those discourses, as well as in the literary accounts and their criticisms, piqued my interest. The questions of representation, framing, childhood, child rights, victimhood, agency, location, publishing, readership, and stereotype loomed large on the screen of mind. I saw rich insights in those works and gaps, distortions, decontextualizations, etc. So, when I did the application for my doctoral programme, I knew the uneasy subject I had to grapple with. I knew I was going to stage an alternative reading of the texts of African child soldier narratives (fiction and nonfiction). Accordingly, I chose this subject because I wanted to understand the forces and discourses informing how we make sense of child soldiering and war in African contexts. I wanted to understand the predominant factors African writers privilege in their recreations of the image of the child soldier in Sub-Saharan Africa. I wanted to apprehend how notions of childhood, child soldier, blameless victim, and rehabilitation initiatives reify and reinforce agelong assumptions about Africa and its conflict situations. I was invested in making sense of why child soldiering in the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries are differentiated from earlier manifestations of the phenomenon and rendered in distasteful senses, especially the African iteration of it.

I was interested in the truths discoverable in the literary representations of African child soldier narratives. My passion for the subject deepened as I discovered its invaluable relevance to how we can appreciate and account for how the current world order came to be. My interest in this subject also thickened because it is a site of scholarly inquiry that is not amenable to one disciplinary tool; it necessitates a multidisciplinary framework that makes a deeper and richer understanding possible. A useful method for an efficient pedagogical practice, too. Once I became immersed in this subject, challenging as it is, it became something I freely allowed to possess me.

The subject of children and warfare and their literary accounts animate me intellectually. I have done numerous conference presentations, organized conference panels, and written journal articles that look at the phenomenon of child soldier representations from different standpoints. The subject is like an elephant; there are different intriguingly complex sides to its bigness. I have done a comparative reading of novels that depict Jewish child soldiers during the Holocaust and African child soldiers, in which I tease out how the different writers respectively shape the images of those beings. The fundamental question that courses through that reading is, why is the Jewish child soldier positively imagined but their African counterpart pejoratively portrayed? There is also the big issue of the concept of child soldiers itself. The oxymoronic construct of “child” and “soldier” and what it includes and excludes interests me. So, I focus on this concept in another article, underscoring the fact that the humanitarian and human rights discourses on the subject wrongly present the idea of the child soldier as essentially a boy, a misrepresentation that predominates literary portrayals of the child soldier. Yet girls have presence in both armed groups and on the battlefronts. In several front covers of books, as well as in their storied worlds, the ubiquitous images of child soldiers discoverable are those of boys. In yet another article, I look at the Afropessimistic framings of Africa in a paradigmatic child soldier novel. My conclusion is that the Conradian spirit, puzzlingly, influences how some African writers represent Africa.

Given your extensive intellectual exertions on child soldiering, you must be worried about the state of the Nigerian, nay African child, today, mindful of the precarious statistics on out-of-school children, malnutrition, and poverty. Is there any hope for them, and what are your prescriptions for an assured future?

Let me also note here that up till now I haven’t stopped being concerned about the adulteration of childhood in Nigeria and other African spaces. I don’t mean to be understood as saying these are the main places on our planet where childhood is endangered. No! The famed developed countries of the West, despite the extant numerous child protection policies, are not assuredly safe spaces for the protection of innocence. Is anyone thinking about the militarization of childhood that the incessant, horrendous gun violence and school shootings in the United States make possible? How about the rampant knife violence in the United Kingdom? When I was writing my book, the Nigerian condition loomed threateningly heavy on my mind. Think about it. If a large conventional war breaks out in Nigeria today, it’ll not lack children and other young people to prosecute it. In other words, as I asked in an op-ed I published in The Nation on Sunday newspaper nine years ago, “can Nigerian child hawkers become child soldiers?” (https://thenationonlineng.net/can-nigerian-child-hawkers-become-child-soldiers/#google_vignette) It’s very well possible. Indeed, the unrelenting Boko Haram insurgency teaches that lesson that the rulers of the country aren’t attentive to.

Nigerian rulers may be declaiming on the accomplishments of their colourless imagination, the staggering number of out-of-school children, most of whom are in the Northern axis of the country, bears eloquent, irrefutable witness to their acute disinterest in functional education. A country is not known by what its leaders claim to have done or are doing. The biggest proof that a country takes itself seriously and is sensibly preparing for its future while meeting the needs of its present societies is how it attends to the mind and body of its young members. If Nigeria prioritizes its tomorrow, it has no business being home to 15% of the total number of the out-of-school children globally. The estimated 18 million plus of children who are not in school show that the country’s priorities aren’t right. My conviction is that there’s hope for children in Nigeria if the politics of belly and death is replaced with the politics of life and development. The country doesn’t lack the resources through which to ensure that its young and adult populations live a decent life that will enable them to be contributors to progress. My recommendation for a better future for children in Nigeria is for governments at all levels to centre the education, health, and security of children in their plannings severally and collectively. They must invest in these humans. They must be mortified by the multidimensional poverty afflicting millions of adult Nigerians and so work to ensure a real change. Nigerians aren’t asking their governments to gift them money; they are asking for such governance that can make them live a decently meaningful life. It isn’t a misplaced ask. But if those who direct the affairs of the country want to keep making children in the land become adult too quickly, then they must be ready to keep contending with the monster of insecurity and violence.

Having completed both your undergraduate and graduate studies in Nigeria, and having taught in its academic institutions, how would you articulate the contrasts – structural, pedagogical, or philosophical – that you have observed between the Nigerian and Canadian educational landscapes?

There are manifest differences between the two educational systems. It’s because of the sustained disinvestment in the Nigerian educational system that makes the Canadian one, as well as others, more desirable to most Nigerians. Otherwise, before the enemies of everything that constituted invaluable knowledge for the formation of minds and socioeconomic development took over the affairs of Nigeria, our educational system was viable. Frontline universities such as the University of Ibadan, Obafemi Awolowo University (then the University of Ife), the University of Nigeria, and Ahmadu Bello University had the universe in them (they attracted the best from across and outside the country) and provided quality learning and research. They functioned to produce minds that were useful for themselves and society. The teachers and scholars in those institutions stood shoulder to shoulder with their counterparts elsewhere. There wasn’t the needless qualification of “Nigerian scholars” that became a thing a few decades ago; they were simply scholars. They were world-class. We weren’t the higher educational system that has now become incapable of respecting the human dignity of its thinkers; our intellectuals weren’t philosophizing on empty stomach; our higher institutions of learning weren’t the anti-intellectual spaces that we’re now forced to deal with; they weren’t places without books; and they weren’t the playgrounds of vice-chancellors who now find it hard to not understand themselves as politicians who see their utmost tasks as self-enrichment and pauperization of the populace. But for the truncation of the auspicious development of our educational system, most Nigerians before, during, and after my generation have no business seeking education and sojourn in Canada or elsewhere. What happened to our educational system in Nigeria is yet to be properly lamented and minded for a change. The Philistines and enemies of functional knowledge are still in town holding court.

To return to the difference between the Nigerian and the Canadian educational systems. Both systems are formatted differently, especially at postgraduate levels. For a doctoral programme in most Nigerian universities, you don’t need coursework, and there are no comprehensive exams that require up to 60 books in each of the two semesters (in some humanities and social science programmes). Whereas in most universities in Canada, you can’t escape these two exercises. These elements in grad school in the Canadian educational landscape are a shock to most Nigerians who make it there. There are always things to let go of from the training received in Nigerian institutions to be able to function in the Canadian one, just as there are many things in that training to leverage to be able to perform excellently in that new learning and research environment. Some of the convenient excuses that have become part of the features of the Nigerian educational system can’t work in the Canadian system. It’s also true that some practices in the Canadian educational landscape can give you a false notion of excellence if you aren’t tracking things properly. In the age of political correctness and ideology of convenience, training and scholarship in Canada can become threadbare. An unhelpful sense of entitlement can creep in as well, based on how some things are set up in this educational system, if one isn’t mindful. Any grad student from Nigeria can function very well in the Canadian educational system if it’s the case that they took themselves and their work seriously in the Nigerian educational setting, warts, and all.

Another point about the difference between the two systems in focus is that in the Canadian variant, it’s unthinkable not to receive feedback on your work as a student, whereas on the Nigerian side of things, feedback is taken for granted. For example, if I know how to move learning beyond the classroom in my own practice, it’s because during my coursework as a grad student my professors enriched me with feedback. That was where I learned the culture of feedback beyond what I experienced in OAU. In my own practice, I centre feedback as an extension of the class. It’s where I stage more knowledge-enriching conversations with my students. And it cuts both ways – we mutually learn more in that process. Never mind that some students neither read nor take the feedback seriously. But those who understand its usefulness justify the efforts one puts into writing that demanding piece by learning from them.

Sadly, in my discussions with students from some universities in Nigeria on my current visit to the country I did hear about some scandalous practices that weren’t full-blown even in my own challenging undergrad and postgrad years. It’s now part of the drill for students to write tests and complete assignments without receiving any feedback and results until after the final exams, in which case the results are released in the term following. If as a student you fail a test, you don’t know it until the next term. It’s even worse if you’re a final-year student. Just when you think you have completed the final term of your study, you suddenly get to know that you have failed one or two courses. How this practice is acceptable is beyond me! Where is the conversation between teachers and learners in this outlandish arrangement? Are the teachers and their students even learning anything worthwhile from one another? How do students improve on anything if they don’t know what they did right and what they got wrong? Just how are they to grow intellectually? How is the education they’re receiving preparing them for the world beyond their institutions of study? Can such students develop any love for their departments or institutions such that they want to aid them after graduation? Just what is celebrated in those convocation shindigs? This somewhat institutionalized act must change.

The other abominable practice in some Nigerian universities that I heard from the students is that some of their professors don’t show up in class. Some turn up only two times in a semester. And some crowd a semester’s work into two weekends of intensive nothing. And they set final exams thereafter! Is this incessant dereliction of duty to be blamed on the government’s defunding of education? I think that if a professor accepts to be part of a system and doesn’t quit because they can tolerate its inefficiencies, it’s inexcusable to neglect their contractual obligations. Some Nigerian professors don’t have the respect of their students, not because they’re inept; it’s because the professors lack exemplary work ethics and don’t have respect for their students’ time. Grad students even have more distressingly terrible experiences from their advisors. Some of these advisors inconceivably delay their students, refusing to attend to their works promptly. In this wise, they remind me of the men one narrator in Chimamanda Adichie’s new novel, Dream Count, describes unflatteringly as “thieves of time.” Those professors rob their students of time, a precious thing. The unfortunate thing is that the grad students of today so robbed of their time and humiliatingly supervised go on tomorrow to become another wicked teachers and advisors who have no iota of respect for the time and effort of their students. They make learning egregiously unappealing to their students. Yes, I understand the impossible conditions under which Nigerian professors labour. But not showing up in class and having no regard for one’s students’ time are behaviours that are difficult to justify and explain away as the problem with the system. They’re unjustifiable! They’re even more untenable in an era where students are now routed through the debt peonage in what is an absurd copying of student-loan system in Western spaces. The respective branches of the Academic Staff Union of Universities must take these disconcertingly unprofessional conducts of their members seriously. Students who are impacted by them mustn’t surrender to fear and silence. The tuition they pay mustn’t be getting them additional ignorance and de-skilling.

As a scholar whose interests span literature and popular culture, how do you interpret the current wave of emigration from Nigeria, often described as a ‘brain drain’? What cultural, historical, or socio-political currents do you believe underlie this phenomenon?

I believe that the Nigerian state is the biggest driver of the emigration wave from Nigeria that you talk about. The love of elsewhere, as some scholars name it, in many Nigerians can’t be divorced from the fact that those who rule the country are only gifted in taking power; they’re habitually grossly unequipped to deploy power to enhance the Nigerian human condition. Keep in mind that the exodus in question is prohibitively costly in many respects. Many lose their savings, they become indebted, they lose familial connections, and they become truly uprooted from where they’ve known for years, and then they go to start again elsewhere. I don’t think anyone who is comfortable in their own homeland would undertake the burden that relocation in recent years necessitates. There must be something about the place you’re moving away from. In the Nigerian case and several other countries with the said wave, the something is the hyena called government; its policies of life devaluation make the country unliveable. I don’t mean to suggest that everyone who emigrates from Nigeria does so because of governmental dysfunction. But what has informed the mass relocations we have witnessed in recent years is the increased government-engineered depreciation in quality living. For some Nigerians who move to other countries, being able to live a simple decent life that isn’t subject to government-induced instability is enough a good reason. How many of our professionals have we lost to different countries because of the Nigerian preventable socioeconomic disasters? It’s now fashionable for young Nigerians who dislike the demands of the life of the mind to escape the country through educational pathways. It’s the same thing for professors who hitherto have enjoyed plying their trades in Nigerian higher institutions of learning; they’re now reduced to doing what they love so much in strange lands. By the way, how did many fine brains in Nigerian universities end up in universities abroad during the successive regimes of dictators in the country? The Nigerian state threatened their safety and, in that sense, caused them to accept job offers from universities abroad. We can talk about other professionals such as doctors, nurses, engineers, and other skilled workers. Unless the Nigerian state begins to travel a different path in regard to how it treats its people and rethink its governance philosophy, many more young Nigerians will be deserting the country. No serious country reduces itself to celebrating the accomplishments of its diaspora citizens whose exit from the country its cruelly facilitated. Why can’t these citizens achieve similar progress in their home country?

Your early professional life was rooted in journalism, a discipline concerned with narrative, truth, and immediacy. How has that journalistic apprenticeship informed your transition into academia and enriched your present research and writing?

I have a person in my life who is a practising journalist of many years. He’s fond of hailing me as a scholar. In response, I’d posit that he himself is a consummate scholar. And he’s really one, particularly given the richness of his mind and what he writes as a columnist. We’re both doing the same work but through different portals. My point is that the work of a journalist inheres in informing the public, enriching people with invaluable information. The practice of journalism requires that the journalist is well-informed. That means the journalist is someone who cherishes knowledge and is given to the continual improvement of their own mind. It requires discipline and rigour. Deadlines are sacrosanct; they must be met. I cultivated these values when I was a journalist. As a matter of fact, I was actively involved in campus journalism in OAU. I began as a reporter for “The Megaphone News Agency,” one of the foremost student-led media agencies on campus. I rose through the ranks to become the Agency’s Deputy Editor-in-Chief and went on later to contest for the position of the Public Relations Officer of the umbrella body of campus news agencies, the Association of Campus Journalists, These platforms prepared me for my work at The Nation newspapers, first as an intern after graduation and later on as a full-time employee. The skills I developed on the job have proved useful in my work as a researcher and teacher. I learned the value of time there; I learned to write for different audiences as a journalist. This skill proves useful when I teach writing. My culture of diligence was developed in my practice of journalism from OAU to The Nation. So, journalism prepared me for the demands of academic life. It built my love of reading and writing and made it possible for me to develop as a public intellectual. I have published many op-eds on subjects of public interest and appeared many times on radio stations as a guest analyst (which I still do). In sum, I think the lesson remains that abilities developed in each job context can be useful in another job area.

The diasporic experience is often one of both dislocation and discovery. What have been the most profound challenges and unexpected opportunities you’ve encountered as a Nigerian scholar navigating life in Canada?

You’re right to describe diasporic experience as heterogenous. It’s both comforting and distressing. In this sense, it isn’t any different from what life is – never a straight-line graph. It’s zigzag and one must mind the uneven flow, for no one is ever promised that life would be through and through a pleasurable walk in the park. That said, I think learning again to exist in a culture that’s manifestly unlike what I have inhabited proved to be one of the challenges I faced when I moved to Canada for my doctoral programme. Reading about a society from afar only helps in some ways. One needs to inhabit it to understand it. But I found quickly that the way I was raised and the training from OAU had prepared me not to be mad when I encounter the strangeness of other cultures.

It was also deeply challenging to find out that not one of the six courses I’d take for my coursework in my home department at the University of Manitoba involved African and/or Black writings and thinkers in any meaningful way. I endured the first semester, but before the second semester began, I sought the approval of the grad chair to allow me to change one of the three courses I’d be in with another course from a different programme on campus. I was granted leave to do so, and that made a significant difference in my learning experience. As a matter of fact, that move proved largely useful for my research on African child soldiering. The course I went for was in peace and conflict studies. The work I did there prepared me well for my research focus. But it was perplexing to find out that African writers and thinkers barely had any place in my department at the University of Manitoba (I enjoyed most of the courses I signed up for though. My professors were excellent minds). But there we were in Nigeria loading our brains with the works and thoughts of other peoples from everywhere in the world, while most of those peoples think little or nothing about our writers and thinkers. Fortunately, that grad-school experience has further shaped my pedagogical inclination. My text selection is attuned meaningfully to diversity. From the University of Manitoba to Mount Royal University I have been more intentional about selecting texts representatively. The education that makes for the development of a round and sound mind can’t be achieved through continual narrow exposure to ideas from the same place and people. I think Olufemi Taiwo puts it better when he submits in his book, Against Decolonization: Taking African Agency Seriously, thus: “How good can scholarship be if it is blind to the experiences of a significant portion of humanity on account of their ‘difference’? Can the ‘best’ scholarship really be productive if it conveniently ignores the ideas of a particular people and the products of their intellectual engagements with questions that have inspired other peoples to create philosophical models?” This’s a point that needs to be front and centre in pedagogical practices across Canadian postsecondary institutions. I have made my choice to be that teacher who introduces his students to ideas from different epistemic systems and by so doing help my students to celebrate and be comfortable with differences while being strong critical thinkers.

As for opportunities in Canada, I’m a beneficiary of many. I’m happy to say that Canada has been good to me and my folks in many ways, its surreptitious but active anti-African and Black racism notwithstanding. It’s not a perfect space. In any case, as humans, we’ll never make anywhere perfect for ourselves. Some fellow Canadians have opened numerous pathways of opportunity for me. I have made another home of Canada. I think my first home prepared me for this second one. And like James Baldwin says of his America, I think I too can say: “I love [Canada] more than any other country in the world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually” and contribute to its continuous advancement.

Canada prides itself on multiculturalism, yet the practical realities of integration are often more complex. From your vantage point, how might Canadian institutions more meaningfully support newcomers from diverse cultural and intellectual backgrounds, particularly those from Nigeria?

One of the many things I like about my fellow Canadians is that they’re aware that our multiculturalism is at best a surface-level reality. In substance, it’s skin-deep. Not even the most dyed-in-the-wool liberal Canadians can heartily celebrate Canada as a steadfast multicultural entity without privately nursing a crisis of conscience. Those who demand fawning appreciation of Canada as a fully accomplished, inclusive emporium aren’t too different from Holocaust denialists. Your politics has to be mean and ruthless for you to think that merely having people from different cultures of the world in Canada equates to being a substantial multicultural state.

That said, I think the needle is moving in regard to making of Canada a truly inclusive state. It’s just that the movement is still being impeded by several forces, one of them being White supremacy and its unfounded demonization of non-White peoples. As such, some suggestions are pertinent. First, those who think for Canada must eschew the idea that they’re doing immigrants a favour for admitting them into the country. For heaven’s sake, these people moved impossible financial mountains to meet the established requirements for admission into the country. To think about immigrants as objects of humanitarianism doesn’t make for the building of a workable multicultural society. Second, having one Black or non-White person in a Whited workplace isn’t the definition of diversity. Neither is one woman among many men a proof of significant variety. Canadian postsecondary institutions, as well as businesses, must be much more serious about creating a real universe on their campuses at all levels. The best places reserved for most non-White people can’t be the back of beyond or, to use a coinage from David Charland’s novel, Brother, the “Scarberia” of workplaces. I think there’s a lot to be gained from ensuring that peoples from the varied racial formations that make up Canada are adequately represented in the different critical sectors of the country. Third, the notion that international students are parasites needs to be retired. It’s a kind of cruelty to think of this group of immigrants as leeches when, in fact, they constitute a major revenue source and pool of human resources for the country. Tweaking policies to make their lives harder in a land that speaks comfort isn’t the way to get the best of them. And may I add that more work still needs to be done in getting the bureaucracy called Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada to completely kibosh its covert anti-African and Black immigration policy. The violence that the “official-unofficial” procedure does to those it’s aimed at is unspeakable.

Cultural identity, particularly in exile or migration, often demands conscious nurturing. In what ways do you sustain your ties to Nigerian heritage, and how do these connections find expression in your personal life and scholarly work in Canada?

I also like this question, especially the concept of exile therein. One thinks sometimes of oneself as being in exile, albeit one inspired by the unnecessarily difficult human condition that bad governance creates. Were the conditions different, there’d be no need to invest in a second home in another land. Nevertheless, it’s impossible to sever ties with Nigeria. Let’s remember that there’s nothing wrong with being a Nigerian. That identity remains, and one is proud to remain connected to things there. Canada can’t avail me with the sociocultural connections that I have in Nigeria. It took years to forge them. As a Nigerian-Canadian, I inhabit two worlds, and I strive to manage their respective demands. I have a thriving family in Nigeria. I still maintain most of my important social and professional connections. I have a conference that I attend annually there, that being the Lagos Studies Association where I was elected to the Conference Planning Committee last year for a five-year term. I’m also a fellow of the Ife School of Advanced Studies, and I participate in its summer affairs. I still collaborate with Nigerian-based scholars. I teach some Nigerian authors. In the last three years I have consistently invited authors from Nigeria to my classes. In Canada, I have a manageable, thriving circle of Nigerians and people from different African countries. And my loop of association involving people of other races is expanding. I think I appreciate the multiethnic, multicultural, and multireligious compositions of both countries. For those who appreciate true plurality and understand that differences aren’t diseases, these similar configurations of both countries are blessings. Policy designers in both places need to make these blessings matter. As one who has teaching experiences in both lands, I also enjoy coordinating classes characterized by multiracialism. Circulating within these two worlds enhances one’s pedagogical and scholarly commitments.

African literature continues to assert itself on the global stage, yet questions of representation, reception, and authenticity persist. How do you perceive the current state of African literary production, and what is its rightful place within the evolving global literary canon?

We had this conversation in Kenya, where I attended the African Literature Association Conference. I had the opportunity to visit some bookstores and participate in one of the episodes of the 2025 Nairobi Festival. It’s a huge delight to me that I was able to access some African literary titles. I saw new works from emerging and established authors. What I want to note with this reference is that African literary production is alive and is being resourced by both writers based across countries on the continent and those in the diaspora. These writers are recreating contemporary African experiences against the backdrop of the continent’s pasts and about many realities of the current world order. Stories about migration and what it means to be African abroad are preponderant. And there are audiences for these works.

However, manifold challenges still plague African literary production. One of the biggest challenges that still exists is availability and access. What I witnessed in Kenya isn’t a reality across the continent. It’s still pretty much difficult to access literary works by African writers in many places across the continent. African literary works don’t have the fortune of being published largely on the continent. As a student at OAU it was never easy to access most of the books we were assigned. But when I moved abroad, I was able to access most of the literary works I had either borrowed from my professors or obtained by other less applaudable methods. It isn’t a commendable thing that African literature is more at home in foreign lands than on the continent. And this has implications for its production. The issue of representation that you mention is a big one when we consider the production locations of this literature and its audience. It’s an open secret that there’re certain African stories that Western publishers privilege; they are the much-talked-about poverty porn, trauma porn, violence, human rights abuses, and other dehumanizing acts through which the single story about the African peoples is reinforced. There is a reason stories of atrocities from and about Africans delight Western publishers. But these are not the only stories that African writers are producing. I think literature, any literature, should not be reduced to the common understanding in journalism that the story that matters is the one that bleeds. No literature from any land should be reduced to a single story of pain and violence. I would also like to see a situation in which African works are available and accessible in different places on the continent. It is not proper to be celebrating the vibrancy of African literature largely outside the continent.

When you contemplate the future of Nigerian communities in Canada and the broader global diaspora, what aspirations, concerns, and possibilities occupy your thoughts?

From what I have observed about Nigerian communities in Canada, I am confident to say their future is bright. These communities continue to make significant contributions to different key sectors in the country. The story is not too different in other countries where Nigerians have made homes. The personal achievements and the roles that Nigerians play in their countries of sojourn prove the point that those who rule Nigeria are the notable barriers to the development of the country. As long as this disturbing situation remains, so long will more young Nigerians seek the comfort of other lands, where they can live more properly as human beings and contribute to the development of those places.

Let me also observe that the tendency of some Nigerians who are now only visitors to the country to insist that any administration in charge of “governance” is doing well needs to be jettisoned. Such positions contribute to why those exceptionally underperforming rulers hyperbolize their tokenistic deliverables as grand accomplishments. It is the case that for far too long successive administrations in Nigeria have prioritized punching heavily below the stupendous financial weights at their disposal. But they have always found people, home and abroad, who consider the politicians’ underwhelming performances as first-rate. One wonders why the Nigerians abroad who laud government in Nigeria left the country in the first place. This band of praise-singers should show a bit of respect for those caught very badly in the throes of life-cheapening governance!

As both a scholar and a community participant, what do you consider the most vital contributions that Nigerians in the diaspora can offer to the social, intellectual, and cultural fabric of Canadian society?

Citizenship is a two-pronged thing. One enjoys the benefits of being a citizen, and one fulfills obligations expected of a national. Nigerian-Canadians cannot be an exception in this regard. Undertaking the responsibilities of citizenship is one of several ways that Nigerians who call Canada home can contribute to the country’s progress. They also have the advantage of knowing another cultural world; they can tap into their knowledge of it to support the advancement of their respective communities. The community is where contributions can be most manifest. There’s always room for positive contributions; one only needs to be observant.

Your poetry has, on occasion, graced both digital spaces and the pages of national publications. Might your readers anticipate a more substantial literary offering—a novel, a collection of poetry, or an anthology—in the foreseeable future?

Lately, I have been considering the promptings of my mind to produce a book of poetry. You’re another person, as if in cahoots with my mind’s nudging, to ask if I have something in the offing. For sure, a book of poetry will happen. I can’t definitively say why it’s to be poetry, especially given my aptitude for the prosaic. And it’s not because poems are easy to write, as some people assume. I think poems that’ll compel readerly attention aren’t ever easy to realize. The collection I’m putting together excites me.

Your work on the representation of child soldiers in literature has garnered wide critical acclaim. Among the responses and reflections, you’ve received, is there one that has particularly resonated with you that encapsulated the deeper intentions behind your work?

Oh yes. Some readers at some of the talks I have given on the book have wondered why I don’t see any good in the activities of humanitarian and human rights organizations concerned with child soldiers in African spaces. It’s a bit of a surprise to me that anyone would understand my argument that way. I don’t see any value in throwing out the baby with the bath water. To be clear, these organizations, which are part of the groups I have, following other scholars, thought of as “BINGOS” – Big International Non-Governmental and Governmental Organizations – from the Minority World do some good work in conflict-riddled parts of Africa. But that work and the thinking that undergird it require critical attention. That’s what I do in my book. I give critical attention to their discourses on children and warfare and their imperious influence on how we understand the child soldier phenomenon and how writers are reimagining it. I don’t think contending that the humanitarian and human rights discourses on African children at war are misleading, de-contextualizing, reductive, and hollow is the same thing as a complete disavowal of the positives in the groups’ undertakings.

Another point I have stressed in response to my readers who think in the said manner is that I don’t think BINGOS should take the centre stage in any country of their operation. Their role should be complementary; that’s it, their intervention should only serve to complement the work of the governments in the countries of interest. It’s a waste of everybody’s time to think that NGOs can develop any country. African countries undergoing political instability or conflict and depend principally on these organizations to transform their countries are only abdicating their own responsibilities. NGOs work well if they’re in support roles. The “ngoization” of development can only serve to indicate puerile unseriousness.

I have also met some people at my talks who did confess that when they first saw the title of my book, they thought that it was another reiteration of the mawkish sentimentality that defines Western attention to children and conflicts in Africa. In other words, until they spent time with the book, they thought of it as another voice parroting the abuse of children at war and those affected by conflicts. And there are those who acknowledge how the book invites them to rethink the idea of childhood and war. It’s also good to know that there are others who disagree with some of my conclusions. I count it all joy; I’d have needed to rewrite the book if all that I have received as feedback is uncritical applause.

It’s been a pleasure having this conversation with you. Thank you for the invitation to do so.